Well over a year ago, the virus we have come to know as COVID-19 arrived on the scene. Not only were our lives completely changed, but it also damaged the world’s economy. Prices were crashing, stocks and assets lost in value tremendously. People lost jobs, and firms went out of business.

Eighteen months on, we start to see the very first signs of recovery in the form of inflation as countries reopen in the bid to return their economy to what it was pre-Covid-19. Inflation is here, and now we question where we will go next.

The sudden crash before an inflationary period is similar to the economic situation during the 2008 financial crisis. We rebounded well from that to build a strong world economy by 2020. We had inflation in the recovery 12 years ago and were ultimately able to control it. It was slow and had early inflationary pressures. Initial signs suggest that we could well be heading down the same path.

But just how similar are the two recoveries, and what can we learn from them?

Economic growth and inflation

2009

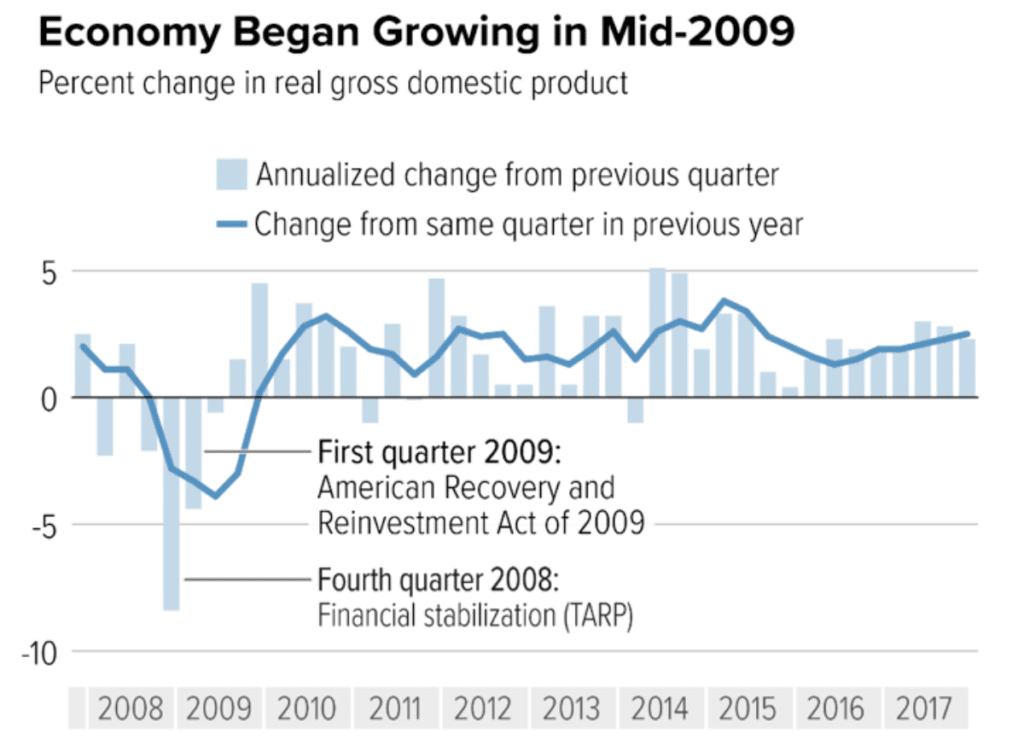

The recovery in 2009 was relatively slow compared to previous recessions. Nevertheless, GDP and inflation metrics did yield some high figures. According to a study in 2018, in the period of nine years after the 2008 financial crisis, the US economy grew an average of 2.2% a year. However, there were spikes up to over 4% at the beginning of the recovery.

Economic Growth in the United States

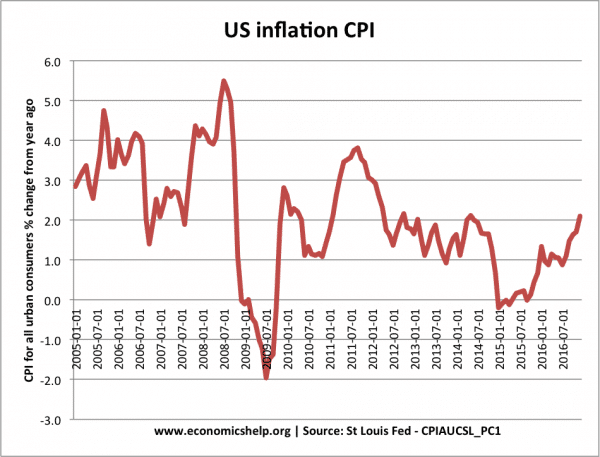

The inflation rate was relatively constant despite a few peaks at 4%. This was largely due to a change in banking regulations and policies in response to the cause of the financial crisis.

Inflation in the United States

The decreased money velocity was combined with the fact that banks tend to be more cautious when lending and borrowing. On top of that, consumers were also more prudent. They were more aware of the threat of a recession and became more cautious with their spending. This decreased the multiplier effect, which contributes to limiting inflation but also posed a challenge towards economic growth.

2021

In 2021, we observe similar economic growth with higher rates of inflation. The peak inflation rate recorded is 5.4%. With the extreme movers removed, inflation is still at 2.9%, which is its highest since 1992, excluding one month in 2008. The figure, 2.9%, is still lower than the peaks of 2009.

There are different factors that can contribute to this. The economy and population have grown bigger. Therefore, the changes might be more drastic. Furthermore, governments are aware of these inflationary pressures but decided against controlling them to keep the economic recovery but also with the belief that the inflation rate will decrease.

The CPI is at 3.70, whereas big inflationary sectors such as food and fuel record up to 5% of inflation. Despite the ‘official’ metrics, many believe that it could be a transitory phase because inflation is not seen in all sectors and commodity prices.

Employment

2009

In this recovery, more than 190,000 jobs were created each month in the United States, totaling 18 million jobs by December 2017. These jobs were not made by the government to artificially stimulate economic growth. The US federal, state and local governments incur a net loss of employment in this period.

Although many jobs were created, the recession also resulted in a high level of unemployment. Long-term unemployment, classified as unemployed for over 27 weeks, rose to 2.6%. This means nearly 10 million Americans were without a job for a sustained period of time.

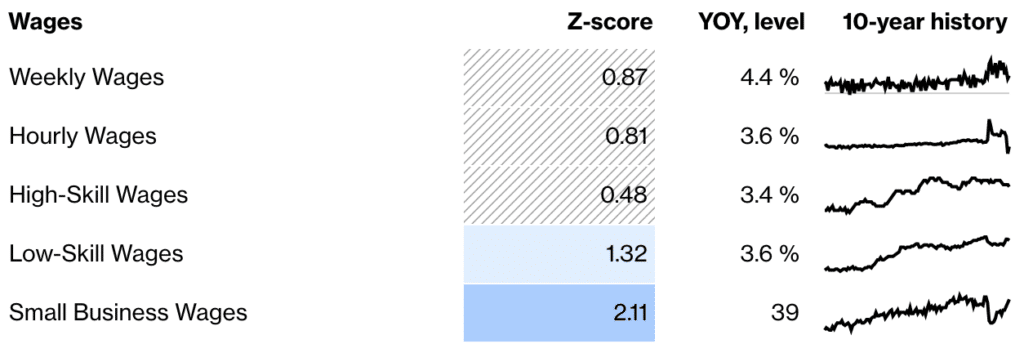

Labour slack was also a big issue. The cause of this is likely the low wage growth which lies at 2.2% annually. As a result, there was a shortage of labour.

2021

The situation is reversed for the current recovery. We are experiencing wage inflation, especially in low-skilled labour.

Inflation of wages

Due to this, there is high job vacancy as it is harder to recruit skilled workers. Along with increased wages, many skills seem outdated after the pandemic, and workers are not as efficient as they used to be.

What’s next?

Many economists expect the economy, with the help of the Fed, to restabilise itself. The bond market seems to share the same opinion. The bond yield curve – a representation of the extra yield investors demand in a ten-year bond against a 2-year bond – is less than 1%, which is less than the rate it was in the last decade. In this period, inflation was under control, therefore, suggesting that inflation will not be a problem in the near future.

There are other reasons that reinforce the belief that inflation will be controlled. Firstly, the Delta variant is very dangerous, and an outbreak can easily cause a recession.

Secondly, economic growth might not be fast enough to keep up with this inflation rate when the unemployment numbers are still high. Therefore, there is no rush for governments to put the reins on the economy just yet.

Bottom line

Although the situations are slightly different, we can see parallels between the two economic situations. Both times, we have a natural deflationary factor: in 2009, it was the banking policies, whereas 2021 is the Delta variant of the coronavirus.

There were and are slight inflationary and employment problems. We seem to be going in the same trajectory, and with the benefit of extra knowledge, it is likely that we can control inflation and recover the economy as we did after 2008.